Yet again, this past week, America faced a new slew of tragic mass shootings. Yet again, American’s heads are hanging low in despair at the senseless brink of lethal absurdity our country now hinges on. Yet again, in the chilling days after these killings, communities are beset with grief and the fingers of cable news anchors and politicians come out to point to non-existent gun laws, mental illness, Trump’s rhetoric, and the hateful violence erupting on 8 Chan. And, yes, yet again, legislation around background checks surfaces as the biggest no-brainer to cross the desks of our Nation’s lawmakers, uh, ever.

But also, yet again, one of the most critical issues contributing to our nation’s sorry state fails to broach public dialogue. Beyond the righteous battle cry against hate is a much more challenging question, both because it pushes against political correctness and because it has to be asked from our hearts: How can we try to understand all this violence and hatred?

The answer many people have is racism, or the toxic cocktail of Trump + racism. They are correct, but that doesn’t get to the root of my question. I’m talking about a deeper understanding of hatred, itself.

Because without any effort to understand all this hatred, to break through to its emotional origins and talk about what it will take to address them, then no matter the legislation or background checks, the problem simply won’t go away.

I’ve given birth to babies (boys) and nursed them. I’ve seen the all too human innocence we all start out with and I’m fiercely on page with Obama in believing that “no one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin or his background or his religion”. But I also believe that along-side love and this original innocence is the all too human emotion of hatred that rises up in each of us. It shows up in all kinds of twisted and hurtful ways precisely in order to protect that original, precious innocence. We are united as humans in our ability to love and also in our propensity to hate. So how, beyond saying it’s bad or wrong, do we make sense of that?

Learning to Hate

I raise these questions as someone who knows hatred well. I grew up the daughter of a father who was a malignant narcissist, the diagnosis unofficially attributed to our President. My father wasn’t quite as bad as Trump, but he shared more than a few of the same defenses our twitter-vicious-gaslighting-reality-distorting president fires off daily. Unlike Trump, though, he didn’t dote on me as his daughter. Rather, my father’s children played the role the Democrats play for Trump — the foil used to prop up his grandiosity.

I grew up feeling powerless, manipulated, unable to find traction to ever fight back. Embroiled in my father’s narrative, there was a point, many of them, really, when my anger gave up, it morphed into something much darker. Black, hard, and cold with the combustable power of dynamite: hate.

With this history I can say with some confidence that by the time you’ve found yourself living with a chunk of hatred in your life, something really shitty has happened to you.

My hatred lived in me for years in quiet, cynical, hostile thoughts, in unconscious projections simmering under the surface of my awareness. I felt scared a lot. I hated men. I masked it well. At times it became self-hate, at others, I turned it back on others. The world was split into good and bad.

Eventually, I came to know this hatred intimately in a different way. In therapy, in meditation and in trauma work I turned towards it and, over time, it played a less corrosive role in my life. At some point, I came to honor it as a teacher that led me to see the deep, human, exquisitely sensitive wound around which it had taken its dark shape.

My experience coming to know and understand hate leaves me clear that any moral outrage vilifying hate will never be the solution.

Had someone told me during my years of deep seated hatred that hate was bad, that I should replace it with love, I would have told them to fuck off. I would have hated them more.

To solve deep seated hatred, you need something that’s harder to come by than advice or moral admonitions. You need vulnerability and that’s the problem. There is no space for vulnerability in today’s political climate, and most of all, in many of America’s men. Among them, of course, American, white men.

But before I go there… a word for my fellow, liberal detractors. If you’re concerned I might start touting some new-age kumbaya poppycock or, worse still, coddle white supremacists, you’ll just have to trust me for a bit. And if you don’t want to do that, then I’d just ask you to ask yourselves if you wouldn’t want to blow the balls of Donald Trump if you could without consequence. Those liberals amongst us who hate the haters (the hypocrisy of which, btw, makes the Right hate us even more) may want to open our minds and start getting curious about hate. Our hate, even. I mean, if we’re so evolved…

But before I go there… a word for my fellow, liberal detractors. If you’re concerned I might start touting some new-age kumbaya poppycock or, worse still, coddle white supremacists, you’ll just have to trust me for a bit. And if you don’t want to do that, then I’d just ask you to ask yourselves if you wouldn’t want to blow the balls of Donald Trump if you could without consequence. Those liberals amongst us who hate the haters (the hypocrisy of which, btw, makes the Right hate us even more) may want to open our minds and start getting curious about hate. Our hate, even. I mean, if we’re so evolved…

Racism: White on Black Inter-Generational Trauma

So, onto hatred. While the last word I have on hatred isn’t about racism, our current situation demands it be addressed first. In My Grandmother’s Hands, Resmaa Menakem lays out the compelling case that America’s earliest white immigrants came from Europe with a traumatic history in their bodies that was forged by ruthless practices of corporal discipline over hundreds of years of European history.

Maimed, beaten, violently diminished by humiliating forms of dehumanizing, public punishment, many white, male Europeans came to America with an unconscious vengeance in their bodies: they would regain their human dignity and eject the trauma that lived in them come hell or high water.

That trauma was poised to be blown into the bodies of ‘others’, dark skinned people who would be forced to carry white trauma in their bodies. Enter racialized trauma. (A whole different ‘arrangement’ supported the superiority of men over women, but that’s another story. Sort of, at least.) Traumatized white people would make these ‘others’ ‘less than human’ so that they could ‘regain’ their ‘humanity’. Black people would now be the lesser ones to humiliate and white dignity could be restored.

Except it didn’t work. No real, human dignity has ever been regained in this arrangement. As the late, beyond great Toni Morrison has said, “If you’re going to hold someone down you’re going to have to hold on by the other end of the chain. You are confined by your own repression.”

The profound disavowal of our humanity — regardless of skin color — lives in our country to this day in an, at times, brutal, master/slave, conscious and unconscious societal fugue. Dark skinned people are turned into “perpetrators and criminals” so white people can avoid looking at their history of criminal perpetration. But, and this can be a hard bridge to cross, this only happens in America because inside all the white perpetrators there’s a victim who’s humanity and innocence was violated — over generations, and continues to be so.

Yes, racism does keep this dynamic alive, it is in-humane and must be called out. We, liberal white folk, furthermore, have to up our game and, more than being ‘social justice advocates’, need to start seeing our white privilege, end the negligence and prepare to start giving something up. But there’s a deep, deep wound that has also been forged in so many, conservatively raised white men that, yes, also needs attention. It’s not popular to talk about it, because God knows they’ve had the levers of power and, for chrissakes, more and more are stepping up as domestic terrorists! (N.B. the Dayton shooter was apparently a far left-extremist.) But if we have no heart open to their reality at all, the war will only go on. It’s a hard question to ask when you are reeling in grief and fury over it all, but what the hell happened to make these guys so mad?

What is Hatred?

So, trauma manufactures hatred which perpetuates more trauma, but what, actually is the hatred when we take a closer look?

Let’s start with agreeing that hatred is. It lives in all of us to a greater or lesser extent. It is human. Some psychoanalysts have pointed to it surfacing in infants in the first months of life when life and death feels like it depends on the presence or absence of responsiveness in our physical and emotional environment (Melanie Klein). Others, like the brilliant pediatrician/analyst D.W. Winnicott, wrote about it as an unavoidable state experienced by the mothers of infants, who naturally would feel feelings of hatred towards their infants after weeks of sleep deprivation, painful chomps on sore nipples and endless demands of their self-sacrifice.

From the perspectives of those in the business of feelings who end up seeing a lot of hate in their patients, the problem isn’t so much with hatred as with our repression and denial of it — our unwillingness to try to understand it.

Human life is a tender undertaking rife with risk and vulnerability, with utter dependence on the mercy and kindness of others. The human heart is an extremely sensitive organ — far more sensitive than our patriarchal culture with its myth of self-reliance has allowed to be known. When we are hurt, neglected, unloved and feel that our rage and anger can’t influence those whom we depend on to care for us, we become terrified, helpless, broken. Hatred is born.

Now, ordinary human hate can come and go in a loving-enough environment, but when fear gets ratcheted up, when resources are in short supply — physical or emotional — when feelings can’t be tolerated in the holding environment, and when young bodies (and adult bodies) are controlled by adults who are threatened by their vitality and respond with harsh, humiliating and punitive punishment, hatred is given a robust breeding ground.

Healing Hatred: Accessing our All-Too-Human Vulnerability

And because of the deep roots of hatred, because it doesn’t show up overnight, hatred doesn’t go away by simply telling people it’s better for humans to love. Sure, in some people this guidance might lead them to put their hate on a back burner for a while – love usually does feels better, for a while. But more often than not, the hatred returns. When it is deep, built up over years, it needs a supportive, safe environment to allow it to be understood — to loosen its grip.

For me, it was therapists, spiritual teachers and other caring people in my life who eventually broke me through to the vulnerability. I needed to un-ravel the story, find the tenderness tucked right up against the fury, that belied the precious and unique heart of me that my hatred had sought to protect.

Part of this journey required actually feeling the hatred, through and through, to its core. I needed to let myself be vulnerable enough to do that — to feel it.

In the end, the process of digesting all that hate— which admittedly took me some years — has changed my life. Over time, I came to see the victim in my perpetrating father and the hidden, hateful perpetrator in my inner victim. After time spent, moment-to-moment, in presence with the actual sensations of hatred, I also came to see that hatred -held in this way- can open you to the deepest core of the human condition: Innocence, beauty, tenderness, vulnerability and then, finally, there it is … love.

But I had to feel and know the hate, to find the compassion for myself and my father in order to get to that real love.

Ironically, then, it was understanding my hatred that taught me compassion — for myself and others.

Understanding more about my hatred has also ended up challenging just about everything I grew up learning about what it is to be a girl, a woman, a man, and a human being on this now, almost human-forsaken planet.

Patriarchal Conditioning

But, again, in case this is starting to sound like some sort of spiritual bypass issuing a romanticized love for humanity, it’s not. I have a fierce commitment to setting things right in the world — but not with moralizing admonitions about hate. Things start to look better in the world to me when we start copping to our humanity. All of it. That means asking the question head on: Why is there not love here? And holding open my heart long enough to begin to try to understand why.

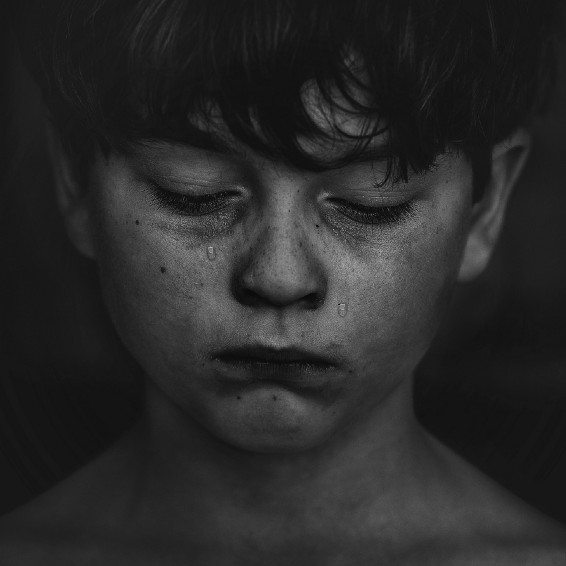

joseph Gonzalez — unsplash

I believe that one of the root causes that perpetuates white supremacy and racism is the harshest of patriarchal standards that flagrantly force boys to disavow their feelings, that harshly sends the message to them in childhood that they are not innocent, but un-ruly and must learn to control their natural vitality or else face the violent discipline they deserve.

This is a model that teaches boys in hard ways to submit to whomever the dominant patriarch is in the family and then tells them to become that dominator when they grow up. The mixed up mess that lives in a strict patriarchal upbringing just hands trauma down from one generation to the next. There is no capacity to process hurt, vulnerability, or any feelings whatsoever. This, combined with a standard for real masculinity that demands self-reliance, control, superiority and respect.

Now, mix this with America’s radically changing demographics, liberal hostility towards right wing, white men, economic strife, women’s empowerment, and the racialized trauma poised to blow out onto people of color and you have a recipe for today’s white violence.

Buried underneath these patriarchal values, and beyond the patriarchal heist of the feminine, are the deep values that have long been attributed to the domain of a deeper, more human(e) feminine — vulnerability, inter-dependence, tenderness, need, embodiment, care. But these domains of human experience don’t belong to women alone. They belongs to no one. They are facts of life. And yet the one thing white men are taught most NOT to be or to feel in life: vulnerable. Here are the shackles that keep our country so divided.

It’s not a popular stance to take among liberals — to ask the question, with any lick of sympathy, about how so many white men in this country (and patriarchal women) got so damn hateful. But we are stuck, interminably, in an impasse if we don’t.

Without condoning violent, racist behavior, we need to find ways to open to the deeper layers where we are human, together.

I know, I know. But these guys aren’t going to start showing up in therapy! You say. But here’s the deal, if we don’t start normalizing vulnerability as part of the human condition more in our mainstream culture — a vulnerability that exists just as much for men as it does for women, immigrants, children, politicians(!) — then we will never make it safe for this nation’s healing to begin.

What’s missing, across the board, in my mind, in news reporting, political discourse, the framing of scientific research, education, mainstream culture writ large, is the normalizing of our universal, all-too-human vulnerability. …What’s missing is a fuller (than patriarchal) account of what it is to be human.

What normalizing human vulnerability looks like.

Whenever I search for a figure in public life today who is finding a way to get this message out, I see Van Jones. I have many times recounted a video I saw of a focus group Van did back during the 2016 primaries. Those in attendance were supporting both Democratic and Republican candidates and Van had clearly made contact with the participants beforehand to ease them up for the interview. In the video clip, Van turned to one young, white man wearing a red MAGA hat. Calling him by his name, relating to him with respect, he asked him why he was supporting Trump. The young man promptly launched into an attack of Hilary Clinton’s criminality and the need to lock her up.

Van stopped him. I hear you, he said, but that’s what everyone else is saying out that. But I want to know what you really feel. I know you have more going on in your life, so tell me, are there things that concern you? That you’re afraid of, that are contributing to your support for Trump?

With this, the young man — who clearly felt seen by Jones with this question— dropped down several feet into himself and began talking about troubles at his church, about an African American friend he was concerned about, his fears about his future. The content wasn’t as significant as the shift in who this young man suddenly became. His face softened, became tender, accessible and we see a guy who’s looking at Van Jones who’s looking back at him in a way it looks like he’s never been seen before. Suddenly, we don’t see a Trump supporter, we see a vulnerable, human being. Someone we may even want to get to know.

I don’t know what happened to that guy after the interview. I just know that something changed for him. What it took was a courageous reporter pointing to something we all, already, know is true.

Americans are scared. All of us. And we need to talk about it at that level — not at the level of morality, right, wrong, partisanship and judgement. We need to talk about how we feel — with vulnerability.

For the last time I’ll repeat it, I’m not saying this to coddle a bunch of angry, white guys. I’m saying it because it’s time to open the field in our country for healing. Time to make it safe for men to talk about what’s really going on in their lives. Time to make it safe by making it more normal.

Written in remembrance of the victims in Gilroy, El Paso and Dayton.